Who am I?

The nature of a person: Now and then

"What is the nature of a person?" Take a moment and think about what makes you who you are. Music lover? Sports fan? Computer geek? Adventurer? People define themselves an enormous number of ways; some examples are below.

- Intelligence

- Sexuality

- Empathy

- Desires

- Religious Views

- Political Views

- Economic Views

- Moral Views

- Student

- Citizen

- Worker

- Member

- Family/Dependents

- Social class

- Race and Gender

- Place of residence

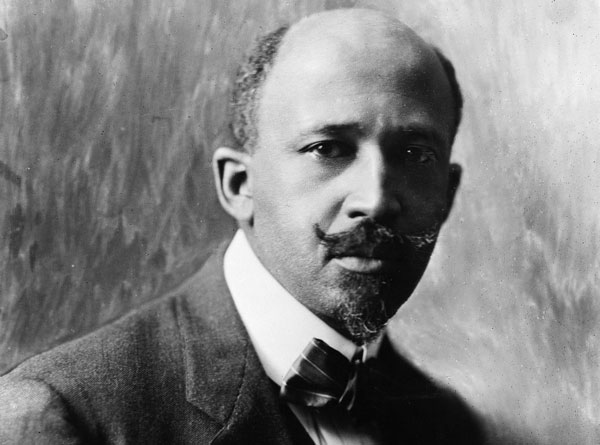

What makes a person is tightly tied to various social, moral and political questions. For example, in the powerful (1903) Souls of Black Folk, American philosopher W.E.B. Du Bois characterised the African American person as suffering from a double identity: on the one hand self-defining as deeply American, and on the other hand self-defining with respect to social prejudice imposed on black people. Du Bois referred to this condition as double-consciousness.

Professor W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963)

But whatever defines a person at any given moment, there is a further question of what makes you the same person at two different moments in your life. This question is misleadingly simple. Are you the same person as your younger self? Dig up one of your baby pictures and look closely at that big head. You're quite different from the little person in the photo. What is it that makes that big head belong to you? What makes you the same person, now and then?

Dr Roberts in 1983

Dr Roberts in 2016

Derek Parfit, in his (1984) Reasons and Persons, characterised the question of identity over time as follows.

"What makes a person at two different times one and the same person? What is necessarily involved in the continued existence of each person over time?" (Parfit 1984, p.202)

This question has moral and political consequences as well. For example, you may feel that your future-self has certain rights: to money that is owed to you, or to the economic opportunity enjoyed by a previous generation, or to inherit a healthy planet. Such questions depend in part on the sense in which that future person is the same 'you'. We may not settle the question today. But, we are about to engage in a classic philosopher's activity: we will develop some new ways to think about the question of personal identity over time.

The Teletransporter: Two Cases

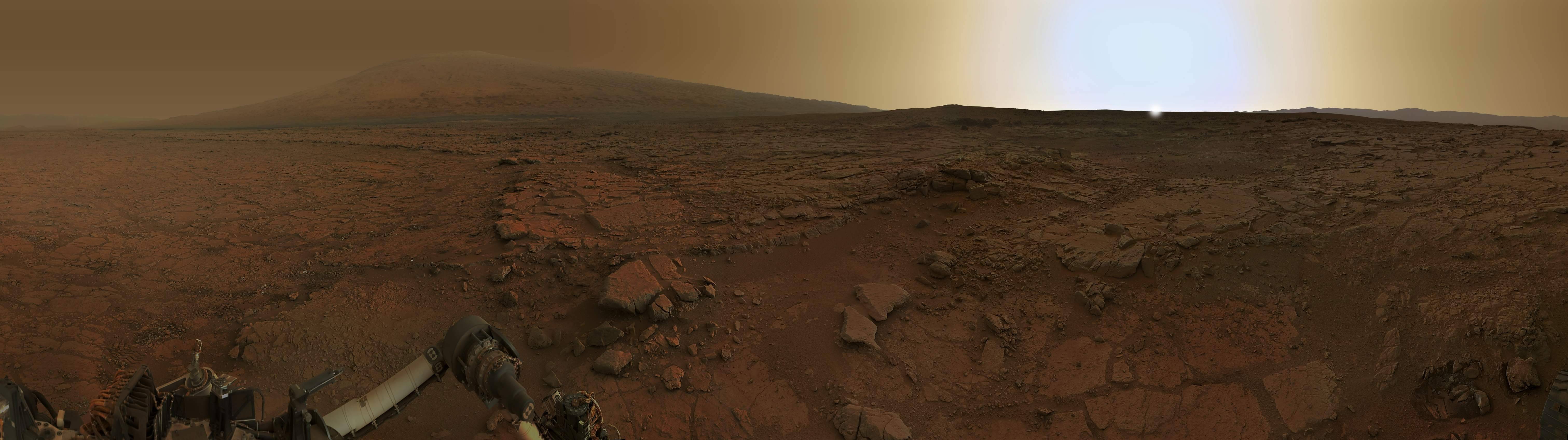

Parfit imagines that someone offers you a free trip to Mars. Great! The details of the trip are below. There are two cases.

Case 1: The Simple Replicator

Here is how your trip to Mars will work.

In the first case, a Scanner will record the data perfectly describing your entire body, with the unfortunate side-effect that it will also destroy your body as it scans. It will then send this data to Mars at the speed of light, where a Replicator will create an exact copy of you. You'll arrive with all of your memories, feeling exactly the same as you did just before being scanned. In short, you will be destroyed and then replicated.

Parfit's Simple Replicator

The Scanner and Replicator are perfectly reliable, and never make a mistake. To begin your trip, all you have to do is step into the Scanner and push the button. Would you push the button?

Case 2: The Branch-Line Replicator

In the second case, a new-and-improved Scanner doesn't destroy your body as it scans. It just sends the data to Mars, where the Replicator makes a second copy of you. However, the Scanner does give your Earth-self an advanced form of terminal cancer, which will kill you within a few days. At this stage, only your Replica will exist, and like before have all your memories and feelings prior to scanning. In other words, you will be replicated and then destroyed.

Parfit's Branch-Line Replicator

The Scanner and Replicator are again perfectly reliable. Would you push the button in this case?

Definitions of Personal Identity over Time

Whether or not you are inclined to push the button may depend on what you think about personal identity over time, and in particular whether you think the Replica is really 'you'. To try to think more clearly about this, let's consider a few attempts to clarify what personal identity over time might mean.

A Physical Criterion: The Ship of Theseus

As a first attempt to understand identity over time, we might focus on the way physical material continues to exist over time. For example, we could say that what makes something like the Parisian restaurant La Maison Fournaise 'the same' over time is that it is composed of mostly the same bricks and wood.

La Maison Fournaise (1881): Bricks and wood

La Maison Fournaise (2012): Mostly the same bricks and wood

You can think in a similar way about your own personal identity. Of course, you might want to say that you are still 'you' if you lose an arm or a leg. In that case, you might say that some appropriate portion of your brain would be enough. Although it's hard to say exactly how much of your brain is enough, we can perhaps bracket this question as something that can be sorted out later, and propose the following criterion of personal identity.

A Physical Criterion: Whatever else is the case, enough of the brain must continue to exist

The physical criterion of personal identity. X today is the same as Y in its past if and only if an appropriate amount of Y's physical composition (e.g. enough of the brain) continues to exist and play the same role in X, and this continuity has not taken a 'branching form'.

Parfit takes a branching form to involve some sort of 'splitting', such as the physical composition of an amoeba splits and continues to exist in two separate forms. Since this results in two distinct amoebas, the idea is that we should not say that they are both identical to the original amoeba — for then they would be identical to each other, which is not the case!

Note that, since the teletransporter doesn't preserve any part of your physical body, let alone your brain, it does not preserve your identity over time:

Teletransporter on the Physical Criterion. "Those who believe in the Physical Criterion would reject Teletransportation. They would believe this to be a way, not of travelling, but of dying." (Parfit 1984, p.204)

The 1st-century Greek-Roman philosopher Plutarch identified a difficulty for the physical criterion, using a famous example now known as the Ship of Theseus.

The Ship of Theseus

Suppose a plank of the Ship of Theseus begins to rot while it is at sea. But, it would seem, the ship is still the Ship of Theseus, just with one new plank. Theseus replaces the bad plank with another one. Later, another plank rots, and so he replaces that too. After about a year at sea, it turns out that ever plank in the ship will have been replaced.

Now is it still the Ship of Theseus? One might be tempted to say yes. It was the same ship at every stage, so it is the same ship at the end. This would require rejecting the Physical Criterion, since no part of the ship has been preserved. But what if, unbeknownst to Theseus, one of his shipmates had secretly been stowing away with the wood at night and rebuilding the original Ship of Theseus piece by piece over the course of the year. Which one is the Ship of Theseus? The new ship, or the one consisting of the original wood?

New Wood

Old Wood

The ship consisting of old wood satisfies the Physical Criterion of being the Ship of Theseus. However, there is still a sense in which the ship with New Wood is the Ship of Theseus as well. It is, for example, the ship that Theseus has been continuously navigating since before he began to replace the parts. Parfit is partial to this latter view, and takes the lesson to be that,

[for some objects,] "their continued existence need not involve the continued existence of their components" (Parfit 1984, p.203).

Why does this matter for personal identity? It turns out that human ageing is like the Ship of Theseus. Your top layer of skin is sloughed off every few days as your body replaces old cells with new ones. Your skeleton is replaced at least once per decade. In fact, except for a few neurons and stem cells, almost all human cells are replaced over the course of your life. And, at the level of the elementary molecules and particles, literally all of them are replaced.

Thus the Physical Criterion has a difficulty describing human identity over time, given the physical facts about how humans age!

A Psychological Criterion: The Teletransporter

To replace the inadequate physical criterion, Parfit proposes that we instead adopt some sort of psychological criterion. One of the earliest such proposals was given by the English philosopher and physician John Locke, who famously wrote in the (1694) An Essay Concerning Human Understanding that,

"Whatever has the consciousness of present and past actions is the same person to whom they both belong" (Locke 1694, 27.16)

One way to put Locke's view is as follows.

The Memory Criterion of Personal Identity. X today is the same as Y in its past if and only if X has memories of the experiences of Y.

This perspective on personal identity has the strange consequence that if you don't remember your actions, then it wasn't you acting. Although this might be seen as good news to those who embarrassed themselves while black-out drunk, it makes for an implausible account of identity.

Parfit gave another reason to reject Locke's view. He began by defining the concept of transitivity, and then gave an argument against Locke, which can be reconstructed as follows.

Transitivity. If X is identical to Y, and Y is identical to Z, then X is identical to Z.

Parfit's Transitivity Argument Against Locke

- If the Memory Criterion of Identity is true, then my future Earth-self is identical to me, and also my future Mars-Replica is identical to me (Branch-Line Case).

- If my future Earth-self is identical to me, and I am identical to my future Mars-Replica, then my future self is identical to my Mars-Replica (Transitivity).

- My future Earth-self is not identical to my future Mars-Replica.

- Therefore, the Memory Criterion of Identity is not true.

The first premise follows by the definition of the Branch-Line case. Both my future Earth-self and my future Mars-Replica remember my current experiences. The second premise is (according to Parfit) a reasonable condition on any adequate account of identity. And the third premise follows from the fact that my future Earth-self and Mars-Replica are by definition two distinct beings, and therefore not identical. If these premises are correct, then the Memory Criterion fails.

Are they correct? You should think this through for yourself!

Parfit moves on to propose an alternative account, which makes use of a more general notion of psychological continuity, rather than a mere memory. He begins with a definition of psychological connectedness.

Psychological Connectedness: a direct psychological connection between X and Y, meaning that X and Y share a qualitatively identical psychological experience (belief, desire, memory, or "any other psychological feature"). A strong psychological connection is an adequate number of such connections.

So, a memory is an example of a psychological connection to your past self. So is a desire. As long as you have an adequately large number of such connections (Parfit suggests that 'half' is a rough guide to strength), then you are strongly psychologically connected to your past self.

Since memories provide an example of strong connections, we know that Strong Connectedness is not generally transitive. So, using the same argument as the one sketched above, Parfit finds that it is not a reasonable definition of identity. However, it can be used to define a psychological account. But first we must introduce a new concept.

Psychological Continuity: The occurrence of "overlapping chains" of strong connectedness.

So, you might not remember much about what you did last weekend, but you remember do remember what happened five minutes ago. And there is a chain of experiences, each of which involves memory of the previous, which leads from now to your past self last weekend. In this sense, you are psychologically continuous with your past-weekend self. This provides now an alternative account of personal identity over time.

The (Continuity) Psychological Criterion of Personal Identity. X today is the same as Y in its past if and only if (a) X is psychologically continuous with Y (through a chain of strong overlapping connectedness), and (b) these connections have the "right kind" of cause, and (c) has not taken a 'branching form'.

Why does the "right kind of cause" matter? Because, quite simply, your memory or psychological experience might have been implanted. Some would then want to say that this is not a "true" psychological connection, since it was caused in the wrong way.

Many falsely 'remember' that the Berenstain bears is spelled 'Berenstein'. It is not.

Many falsely that the monopoly guy has a monocle. He does not.

Parfit distinguishes three kinds of approaches to causes of our psychological experiences.

- Narrow version: Right kind = normal cause

- Wide version: Right kind = any 'reliable' cause

- Widest version: Right kind = Any cause

Which approach one takes has implications for the Replicator experiment: "The Replica is me" is true on the wide and widest versions, since the Replicator is reliable, but just not a normal cause. "The Replica is not me" is true on the physical and narrow versions.

Parfit Against Identity and For Relation R

What is Parfit's view in the face of all this? There is a positive and a negative part.

The negative part is that for considerations about your future self, identity doesn't really matter. You don't have to try to answer what identity "really means" in any practical sense. There needn't even be an answer to a question like, "Is the Future-Replica really me, or is my Future Earth-Self really me?"

The positive part is that psychological continuity and connectedness does matter. Parfit refers to this as Relation R. The Replica cases may seem strange, but they are just different examples of how a person may persist in time.