An interesting sense of time travel

We said that we would study metaphysics, the study of the nature of reality. And since much of what we might consider is set in time and space, we might as well begin by studying time, and then turn to space. Our philosophical adventure this term will begin with the question of time travel.

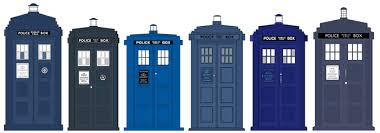

There are lots of things that one might mean by "time travel." Some of them are trivial. For example, someone might say, Look! I've traveled forward in time several seconds since arriving at this text! Fine, that is certainly the case, but it isn't interesting. We want an interesting sense of time travel, of the kind that "the Doctor" and other science fiction stars captivate our attention with. The kind in which you travel to ancient Egypt, or give advice to your past-self, or visit an advanced future civilization. Is this kind of time travel a serious possibility?

There are lots of things that one might mean by "time travel." Some of them are trivial. For example, someone might say, Look! I've traveled forward in time several seconds since arriving at this text! Fine, that is certainly the case, but it isn't interesting. We want an interesting sense of time travel, of the kind that "the Doctor" and other science fiction stars captivate our attention with. The kind in which you travel to ancient Egypt, or give advice to your past-self, or visit an advanced future civilization. Is this kind of time travel a serious possibility?

Visualizing travel

David Lewis begins by asking how we might visualize time travel. He suggests the following picture, which is very helpful indeed. Let's begin by just visualizing the motion of a normal traveler. Start by imagining a "spatial" dimension. It could be a man and a tree separated by some distance, as below.

What do these objects look like as time passes? Let's call the vertical axis the "time" axis, and redraw these objects at each later moment in time, as on the left below.

So much drawing can be tedious, so let's adopt a shorthand of just characterizing their paths as lines. The resulting "streaks" (as Lewis calls them) describe how things pass through time. They illustrate to objects that don't move at all in space. The language of "streaks" that Lewis uses is idiosyncratic; it is more typical to refer to them as world lines in physics and the philosophy of physics.

Worldlines can describe lots of interesting motions, and are very commonly used in physical theorizing. For example, here are the world lines when the man walks up to the tree and then back again.

Visualizing time travel

It's worth playing around with world lines until you become familiar with how to draw objects in motion. But let's get straight to the point. What kind of scenario would be described by the following worldlines? They are all time travel worldlines in one way or another.

Each represents an interesting sense of time travel. Think through the kind of scenario that each of them describes. Dotted lines are drawn in the second and third diagrams to represent what Lewis calls the "continuity" of a time traveler's identity. That is, there must be some sense in which it is the very same person at all moments in the time-traveling adventure.

This is the kind of time travel that Lewis is interested in.

Notice that time travel allows some very strange scenarios. For example, a person might use a time machine to travel back and tell her past self how to build a time machine. It is only with knowledge that the person's later self is able to actually build the time machine and go back. Where did the information about the time machine come from? Lewis says that "[t]here is simply no answer." It is a strange story, but a possible one, there is simply nothing else to be said. This is the core of Lewis' thesis.

Personal Time vs External Time

What makes these world lines time travel worldlines? According to Lewis, it has to do with two distinct notions of time: external time and personal time.

For Lewis, the time axis is the "one true" concept of time that characterizes our world. This is external time. Everyone agrees on how much external time there is between any two events, according to Lewis.

On the other hand, personal time is a measure of time that tracks an individual worldline. For example, an observer might be carrying a watch, which ticks normally throughout a time-traveling episode. Or, one could count the beats of the observer's pulse, or measure the length of her hair, or any number of other things in order to characterize how much time an observer "feels" to have passed.

The definition of time travel, according to Lewis, just that an observer's personal time disagrees with the external time. For example, according to a traveler's personal time, she might invent a time machine and then go visit ancient Egypt. But according to external time, she was in ancient Egypt and later invented a time machine.

The Grandfather Paradox

As fun as time travel may seem, there is at least one major potential problem, known as the grandfather paradox. It takes the form of the following argument.

As fun as time travel may seem, there is at least one major potential problem, known as the grandfather paradox. It takes the form of the following argument.

Suppose first that if it is possible for you to time travel, then the statement "you exist" is true. Plausible enough. Now, assume further that time travel implies that you can do whatever you want while time traveling. In particular, you can travel back to a time and kill your grandfather before he met your grandmother. Then he could not give birth to your parent, who then could not give birth to you. So, the statement "you exist" would be false. This is a contradiction: the statement "you exist" cannot be both true and false --- thus we have a paradox.

What are we to conclude from the grandfather paradox? We cannot live with a contradiction. So, we must reject one of the premises of the argument. And, someone might say, the most plausible thing to reject is surely the premise that "time travel is possible."

Escaping the Paradox

Lewis points out quite correctly that there is another premise one can reject. Namely, one can reject that it is possible to do whatever you want when time traveling. You can time travel back and try to kill your grandfather. But as a matter of fact, given the way this story started, you will not succeed. Your gun will jam, or you will trip and miss at the last moment, or you will have a change of heart. But you will not kill your grandfather.

Lewis likens this to the sense in which he can and cannot speak Finnish. (David Lewis was a native English speaker and never learned Finnish in his life.) He can speak Finnish given certain facts about his biology and cognitive abilities. But he cannot speak Finnish given a certain other fact, that he has never taken the time to learn.

Similarly, the idea goes, you can kill your youthful grandfather given the fact that you have aimed a loaded gun at him. But you cannot given the fact that he is your grandfather.

Some physical problems with Lewis time travel

Thwarting the grandfather paradox does not mean that Lewis-style time travel is coming to an Apple store near you. There are at least three problems facing the Lewis proposals for time travel. Recall again the three time travel diagrams above.

Begin with the left diagram. Remember that a vertical line represents an observer that stands motionless, not moving in space. As the line tilts to the right, the observer's speed increases. So, what happens when the line tilts completely horizontal? The speed is infinite. But horizontally tilted lines are required in time-travel diagrams like this one, in which a world line "turns around" in time. So, the first instance of Lewis time travel requires infinite speed. But that is physically impossible.

Second, in the remaining diagrams, the notion of continuity is vague at best, and at worst implausible. Some kind of continuity between world lines is needed in order for us to say that there is a traveler (time traveler or not). So, what is the notion of continuity in play here? Lewis suggests it might be continuity of memory. But, given the sci-fi nature of our time machine, this may not be enough to convince us that there is really one continuous traveler.

Third, this account is not compatible with Einstein's theory of relativity. You do not need to concern yourself with the details of this theory; that is another course. But it is enough for you to know that one of the important things that relativity taught us about the world is that "external time" is a fiction. We do not generally have anything like the "one true time" against which to compare all personal times, and so the very definition of time travel according to Lewis may be questionable.

Is there any way to save time travel from the force of these worries? Perhaps; this will be our topic for next time.