The 'Scientific Method' for children and the HD Method

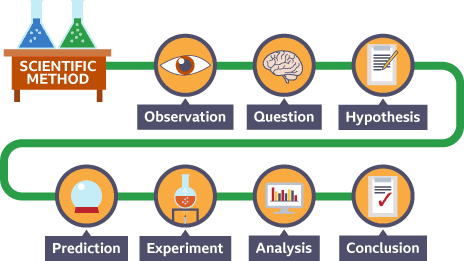

We teach children that science has a unique methodology of using empirical evidence to support its claims, often called the The Scientific Method. For example, you here is a version of the method described in BBC BiteSize teaching materials for 11-14 year old school children in UK Key Stage 3 (KS3).

Image Credit: BBC BiteSize KS3 'Writing a hypothesis and prediction' (2025)

This account turns out to be exactly what philosophers of science call the Hypothetico-Deductive (HD) Method from our discussion of induction and Hume's problem:

- Propose a hypothesis.

- Show that the hypothesis implies a testable prediction.

- Check whether empirical evidence matches that prediction.

- If so, then the hypothesis is confirmed. If not, then it is falsified.

As we saw last time, this account suffers from serious problems, such as the Paradox of the Raven: the HD account seems to allow totally arbitrary observations, like 'This shoe is white', to confirm the hypothesis that 'all ravens are black'.

Another issue is the problem of coincidence: you might have heard of the late Paul the Octopus, an English octopus from Weymouth who became famous for his 2010 World Cup predictions in Oberhausen, Germany. For each of the World Cup matches involving Germany, Paul would be given two boxes of food. The boxes were identical except for the flags of the teams displayed prominently on the front. Each time, Paul would choose to eat from one box of food first. Each time Paul chose the box displaying the flag of the team that would win the day's match. If Paul's choices were random, then his predictions were equivalent to correctly predicting the outcome 7 coin tosses in a row, for which you have a roughly 1 out of 125 percent chance.

Paul the Octopus: World Cup Oracle?

Now, suppose your hypothesis were, 'Paul the Octopus is a football oracle capable of predicting the outcome of any World Cup match.' Then the HD Method would seemingly lead you to confirm this hypothesis!

But would you have trusted Paul with matters that are really important? With your choice of university? With your choice of lover? With your choice of job? I'm guessing that you would not. Paul is just an octopus. He did have a remarkably lucky run on a few isolated occasions, but his success rather seems to be a coincidence, and the HD Method is not strictly correct

If the HD account of scientific confirmation is not exactly correct, then what is? This is the philosophical problem of scientific confirmation: how exactly does evidence justify a scientific hypothesis or theory? Philosophers have given a number of answers. However, as we will see, the correct answer is very much an open problem in philosophy of science.

Popper's anti-inductivism: Reject confirmation

Popper's View

We need to either produce a more sophisticated account or give up on induction entirely. Karl Popper chose the latter. So, let's briefly consider that option before returning to the former.

Sir Karl Popper (1902-1994), who founded the LSE Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method

You have probably heard of Popper's most famous catch-phrase, real science must be falsifiable. His advocacy of this view had an long-standing influence on scientists in both the natural and social sciences, in part because of Popper's extensive engagement with both at LSE. However, this is not what Popper was saying, nor is it even his idea.

As you know from our discussion of Modern Empiricism, the logical empiricists were demanding that meaningful statements be subjectable to empirical tests, which could involve either verification or falsification. The main thesis that Popper advocated was to deny that verification is possible according to schemas like inductive confirmation. In other words, Popper denied the possibility of inductive confirmation.

How naïve induction can lead scientists astray

Popper was in part concerned with the lack of a reason to believe that induction works, much like the predictive powers of Paul the Octopus. But he was also concerned that inductive confirmation was responsible for some of the greatest failures of science.

For example, physicists George Ellis and Joe Silk published an article in Nature some years ago arguing that, due to the systematic tendency of many recent theories of physics to be adjusted or "tuned" so as to match almost any data whatsoever.

Ellis and Silk gave a recent theory called supersymmetry as an example. All you need to know about it for this discussion is that supersymmetry includes claims about what kinds of particles there are. But, according to Ellis and Silk, proponents of supersymmetry can always adjust the taxonomy of particles to match observations, no matter what we happen to observe.

The problem is that a theory that can account for anything accounts for nothing at all. It can describe falsehoods as well as it can describe truth. There is no reason to trust it.

A Popperian would say: the source of the problem is inductive confirmation. To avoid it, he argued, one must believe only what has been falsified and not what has been "confirmed". That is, one must deny the possibility of inductive confirmation. To do otherwise leads one to the belief in illegitimate accounts of supersymmetric particles and octopus oracles.

Popperian Corroboration

Of course, Popper did think that some theories were more worthy of our consideration than others. The theories that had this character were said to be corroborated. However, one must not mistake corroboration for confirmation. Induction gives us no reason to adjust one's belief in the truth of a theory. At best, it suggests theories that are worthy of our consideration.

Popper's view is extremely radical, much more so than the simple slogan that science out to be falsifiable. It denies much of what many scientists believe, that we have reason to believe in the truth of some of our best theories of science, which is the subject of the realism debate.

The Pittsburgh philosopher Wesley Salmon summarised its most serious difficulty: we use induction to guide our predictions in science, a practice that seems to make absolutely no sense on Popper's view. A theory having been "corroborated" and thus made worthy of our consideration provides no reason whatsoever to believe that it will make the correct predictions. On the other hand, if a theory receives inductive confirmation, then we have more reason to believe that it is true than we did before, and so we are justified in using it to make predictions.

Perhaps all that is needed, then, is a more sophisticated account of inductive confirmation. Let us turn to the possibility of such an account now.

Keep Induction: Bayesian Confirmation

Instead of giving up on the HD Method entirely, suppose instead that we add structure to our account of induction to correct some of its shortcomings. A simple and obvious idea, so helpful that you may have thought about it already, is to make confirmation a matter of degree, just like a probability.

Instead of asking whether evidence confirms a hypothesis, we will ask to what degree a hypothesis is confirmed, on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 1 (certain). It's just like the way that accumulating evidence of a courtroom can gradually increase the jury's belief that the defendant is guilty.

On Bayesian accounts, confirming evidence builds as a matter of degree, just like evidence at a jury trial.

How much is our belief in a hypothesis raised or lowered when we receive a piece of evidence? It depends on what kind of evidence it is. One normally describes the situation as follows.

Say you're interested in a hypothesis H, such as "It will rain in London today", and that we're considering the evidence E that "There are no clouds in the sky this morning". How much should the evidence of the clouds adjust your belief that it will rain?

Let's take a concrete situation of 9 days in London, each represented by a square in the grid below.

The blue and brown squares in the diagramme indicate the portion of days that it rains in London, roughly 4 out of every 9. So, without any further evidence, there is a 4/9 = 0.44 or 44% chance of rain. This is called the prior probability of rain: it is the basic probability before any evidence is introduced.

Now let's see what happens when we introduce evidence: suppose there are no clouds in the sky. In the diagram, this means we are now restricted to the three white and blue squares where there are no clouds. Since two of those days are rainy, we can conclude: given that I've seen clouds, there is a 2/3=0.66 or 33% chance of rain.

If this diagramme is accurate, then seeing no clouds in the morning provides confirmation for the theory that it will rain. But, we can actually say something much more precise: the evidence increases our confirmation from 0.44 to 0.66.

This situation is described precisely using conditional probability. Confirmation occurs when a piece of evidence E increases our belief in a hypothesis H if the probability of "H given E", written P(H|E), is greater than the probability of H alone, written P(H). In the case above, we found that P(H)=0.44 and P(H|E)=0.66, so this is an instance of confirmation.

On the other hand, disconfirmation occurs when a piece of evidence E decreases our belief in a hypothesis H, in that P(H|E) is less than P(H).

The view that probability theory can be used to describe the confirmation and disconfirmation of a hypothesis in science is known as the Bayesian approach to confirmation. It is at the same time an extremely general approach to confirmation, as well as an extremely popular approach among philosophers of science. It may be summarised as the following two principles:

- Inductive confirmation is a matter of degree (between 0 and 1) that satisfies the axioms of probability.

- The degree of confirmation that a piece of evidence E gives in support of a hypothesis H is given by the conditional probability Pr(H|E).

One advantage of this revision of inductive confirmation is that it makes immediate sense of the Raven Paradox discussed last time.

In particular, we now have now problem saying that observing a white show confirms that all ravens are black. The degree of confirmation is just exceedingly small. Although we have narrowed the number of non-black things that are non-ravens, the enormous size of this class of things means that it does little to confirm that all ravens are black. Observing a large portion of the total number of ravens, on the other hand, provides a much larger degree of confirmation on the Bayesian approach.

Difficulties with Bayesian approach

There are a number of well-known difficulties with the Bayesian approach.

- How do we set the probabilities in the first place? We could only do our calculation with the rain because we know the portion of days that it rains, the portion of days that its cloudy, etc. How do we assign these probabilities? The Bayesian account provides no way to do this, and it is not obvious how any particular way to assign probabilities can be justified. This is called the problem of the priors — no "prior" probability of a hypothesis P(H) is not justified on the Bayesian account.

- No way to describe ignorance. On the Bayesian picture, P(H)=0 implies a hypothesis has been falsified with certainty, while P(H)=1 implies that it has been confirmed with certainty. P(H)=1/2 implies that there is an equal chance that the hypothesis be true or false. But nothing is said about the situation in which one is completely ignorant. For example, suppose you have a coin that you suspect is biased, but you have no knowledge whatsoever about that bias. What probability should you assign to the outcome that it lands heads? The Bayesian approach has no way to even describe this situation, let alone make a prediction.

- Probabilities cannot always be assigned. The current universe is thought to be spatially infinite. But all probabilities of events occurring in finite regions of an infinite universe are zero. So, no non-trivial probabilities can be assigned in this context. Nevertheless, scientists are able to do cosmology and collect evidence about the universe as a whole. The Bayesian approach has no way to describe this.

Norton Against Universal Schema for Confirmation

John Norton points out that there are three main approaches to induction so far on the table.

- Naive Induction, which has the problems discussed last time of lack of sophistication.

- The Hypothetico-Deductive Theory, which falls prey to problems like the Raven Paradox. (Norton views Popper's falsificationism as a radical special case of this theory.

- Bayesianism, which gets stuck on the problem of priors, among the other problems described above.

According to Norton, the problem with all these approaches is that no inductive inference schema can be expected to work in every case. The main argument for this, he says, is that it is the only reasonable response to a paradox due to Mill, which goes as follows.

Consider any argument that bismuth melts at 271°C, and compare it to any inductive argument that wax melts at 90°C. As an example, let's adopt the simple naïve inductivist argument scheme, although Norton argues that any universal schema for induction will suffer the same fate:

- Observation: Some samples of bismuth were observed to melt at 271°.

- Conclusion: All samples of bismuth melt at 271°.

Some bismuth samples

- Observation: Some samples of candle wax were observed to melt at 91°.

- Conclusion: All samples of candle wax melt at 271°.

.jpg)

A wax sample

These sentences have exactly the same grammatical form. And any argument concerning them that uses the approaches to induction above will have the same logical form. So, these general approaches to induction should generally take these two statements to be equally confirmed.

But this is absurd — although it is a chemical fact that Bismuth always melts at a fixed temperature, there is no such guaranteed fax about wax; indeed, wax melts at many different temperatures, and which temperature it is depends on its precise composition.

Different kinds of candle wax melts at different temperatures.

Thus, Norton concludes, there is no universal schema for inductive inference: not HD, not Bayesianism, not Inference to the Best Explanation— not anything.

The Material Theory

The lack of a universal scheme for scientific confirmation still allows the possibility of a 'local' (not universal) account. Norton proposes one such account, and defends it in detail in his book The Material Theory of Induction, which is available to download for free open access.

Norton claims that what distinguishes the bismuth example from the wax is a hidden premise of the inference, which scientists don't always make explicit but which in this case is definitely there. Namely: in most cases, all samples of the same chemical element have the same melting point. In other words, once the hidden premises are restored, we see that the two inferences above actually look like this:

- Material Fact: In most cases, all samples of the same chemical element have the same melting point

- Observation: Some samples of the chemical element bismuth were observed to melt at 271°.

- Conclusion: All samples of bismuth melt at 271° (in most cases).

- Observation: Some samples of candle wax were observed to melt at 91°.

- Conclusion: All samples of candle wax melt at 271°.

.jpg)

Once the hidden assumption is made explicit, it is clear why the two arguments are different: the bismuth argument is a deduction that is as secure as its premises. If the premises are true, then the deduction is true.

The fact that there is no universal schema for induction, according to Norton, arises from the fact that this inference's real justification lies in the hidden premise, which is entirely 'local' or specific to the specific science in which it arises. This, in is the material theory: scientific confirmation is powered by observation together with local, material facts.

Norton gives a number of examples of how an inference from `some' to `all' was powered by local material facts in the history of science:

- The inductive inference to the existence of Neptune was powered by Newton's laws

- The discovery of the tides was powered by Newton's laws.

By now you may be wondering, of course: what justifies the material facts? In this case, Norton's answer is the same as before: material facts are justified in the very same way, by an argument powered by observation together with further material facts.

Now you may be wondering if there is a danger of a regress. Norton admits that this regress exists, but does not think that it is too dangerous. He assumes instead that such a regress will eventually "bottom out" with facts that are justified by brute observation, with no further inductive steps needed. The success of his account therefore depends on whether or not this is possible. Is it?

Norton himself discusses this more in his Section 6, and at length in his book. I will leave to you to decide.

What you should know

- Popper's anti-inductivism and its problems

- The Bayesian approach

- The Bayesian problem of the priors, problem of ignorance, and problem of not being able to assign probabilities.

- Norton's material theory, and Norton's solution to the regress problem.